Into the underland.

On how to move forward.

“Into the underland we have long placed that which we fear and wish to lose, and that which we love and wish to save.” – Robert Macfarlane, Underland

Dear reader,

Let us begin as we always do—orienting in Place and Time. I write to you from one thousand miles south of my home nest, from the Central California coast, journaling on the same rock, sheltered by the same little aquamarine house where I landed to rest exactly one year ago. I spent January 1, 2025 here; now I’m back, editing this essay on December 31. Beginning and ending the same year in the same place on two separate visits that feel like two separate lifetimes. And yet, the flowers here still arc toward the same sun.

If you’re trying to remember something, someone, stand near a eucalyptus tree.1

One year ago, I wrote the essay Braid me back to Life, kicking off a three-month sabbatical that would turn into me quitting my job and embarking on a new solopreneurial era of lifelong work. One with ample rest built in, abundant autonomy, and the sovereignty to, to the best of my ability within modernity’s impossible demands, actually embody what I’m in service of.

Nevertheless, my work and my Self still seek dormancy. Ideas require incubation; strategy requires review and recalibration; bodies require, well, so much and yet so little. Annie Dillard perhaps describes the mind-body dynamic best in her essay, Total Eclipse, recounting going out to breakfast after witnessing, yes, a total solar eclipse:

“‘It can never be satisfied, the mind, never.’ Wallace Stevens wrote that, and in the long run he was right. The mind wants to live forever, or to learn a very good reason why not. The mind wants the world to return its love, or its awareness; the mind wants to know all the world, and all eternity, and God. The mind’s sidekick, however, will settle for two eggs over easy.

The dear, stupid body is as easily satisfied as a spaniel. And, incredibly, the simple spaniel can lure the brawling mind to its dish. It is everlastingly funny that the proud, metaphysically ambitious, clamoring mind will hush if you give it an egg.”

Laptop open, eating a fried egg while I type to you, I’m grateful that this little aquamarine house has become akin to what the breakfast diner was to Dillard: “…a halfway house, a decompression chamber” for a mind reeling in deep space.

It’s a place where I can come to write with fewer distractions and more lemon trees around me; where I’ve had the immense pleasure of simply witnessing the hours pass by, tracing the sun and moon across the sky; it’s near where I sat in my first (and maybe last) 10-day Vipassana—a potent container for the simple, excruciating, liberating task of observing only what is.

I’d like to say this place has become an annual respite, and yet, this year, everything follows me here. Even you. Especially, you.

I’ve decided I’m only going places I can access by two feet, two wheels, or one long, fiberglassed piece of foam. Following the sun from the east-facing cliffs to the front stoop to the nearest west-facing feature. Avoiding any action that comes with the word “should” in front of it.

I deleted all scrolling apps for the week I’m here—no Instagram, no Facebook, no Substack. That leaves Photos for my dopamine-addicted brain and its sidekick—thumb. Fitting for a trip saturated in reflection and memory.

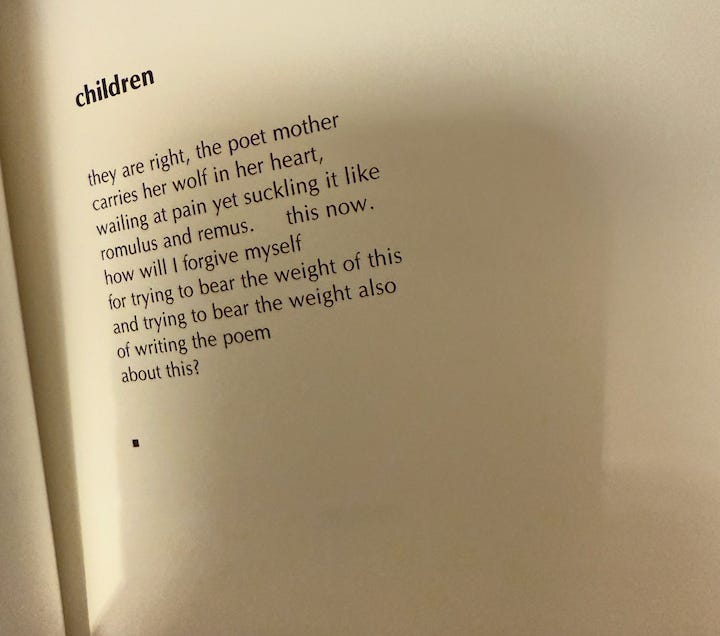

In sifting through photos from a year ago, on this same couch, from this same couch, I came across this Lucille Clifton poem:

Clifton’s searingly simple yet deeply textured writing stands as a track-stopper on its own. Layer on personal and temporal context and it takes on a whole new, gorgeously gut-wrenching gravitas.

Dear reader—this poem is exactly how I feel right now. There is very little between these words and myself, and whatever it may be, I could dissolve it between my fingertips.

“This is me now, not then,” I tell myself, baffled. “Not then. This wolf, this wailing—they were not here when I was a year ago.”

And yet—they were.

They were enough to move me to preserve this poem in the way one does in the digital Anthropocene—with an iPhone, with a one percent chance of it ever being organized, left to drift in sea of thousands of photos unlikely ever to be revisited, sorted, or revived again, taking up space on a red hot server.

I ask, “Is this one of those Time-folding-in-upon-itself moments where Future Me traveled backwards in order to leave Current Me a clue in this exact same location, as Past Me had no idea of the heartbreak that was coming?”

Or has the Mother’s grief, the World’s grief, actually always been this close? Is it even a different pain at all?2

Dear reader, what does a New Year require in non-linear time? When the smell of the eucalyptus demands you get off your rusty pink bicycle, travel back in time, and weep? When the sorrow, no, the split parts of yourself, no, the child self that you still carry, asks for your breast? Who, what, which story do you feed?

+

By now it’s early January—the time of year when capitalist overculture tells us to look ahead. Start fresh. Move on! Forget! Stay distracted! New! Bigger! Betttttter.

January, named for the ancient Italic deity Janus, the Romans’ guardian god of portals, doors, and gates; patron of beginnings and endings.3 He is often depicted as having two faces, one in the front and the other in the back.

In Jewish time, we find ourselves halfway through the month of Tevet, whose Hebrew etymology connects to “sinking,” “immersion,” or “mud.” It is a time to move slowly. To trudge. To stay low, with gravitas. (Gravis, meaning heavy, the same root word for grief.)

In sky time, the sun moves through Capricorn, symbolized by the seagoat—two front legs diligently marching uphill while its tail remains submerged in emotional, yin-time waters.

In North Olympic Coast time, we are barely two weeks past the winter solstice. Darkness still reigns 16 out of 24 hours, slowly retreating by five seconds per day.

Can you feel them?

The hibernating bears are still asleep with a heart that beats once every 20 seconds.4 That’s four backward paces of Darkness within one forward pulse of the hibernating heart.

Perhaps where we are supposed to be is exactly right here, right now. Parts of ourselves gazing ahead at best while the bulk of us remains immobilized, looking backwards. Perhaps there is nowhere else to go—yet.

Before you suggest it—I’m reading Francis Weller’s The Wild Edge of Sorrow, again. Rilke finds me there, unsurprisingly, with his poem, Pushing Through:

“It’s possible I am pushing through solid rock

in flintlike layers, as the ore lies, alone;

I am such a long way in I see no way through,

and no space: everything is close to my face,

and everything close to my face is stone.”

It is a time-bending gift to feel so seen by a person who you will never physically meet, who lived and wrote about what you’re experiencing more than 100 years ago. Again, now and then meet.

Grief is a cave-like experience that can feel like a trap—walling you in, inescapable, limbs wedged between boulders. Like you, yourself, might turn to stone.

Yet there is a difference between being afraid and becoming petrified.

Petrification takes place when an organism is rapidly buried, cut off from oxygen, and unable to decay. Mineral-rich water pours into its empty spaces, gradually replacing the organic molecules cell by cell. The minerals crystallize; the form becomes stone. It keeps things as they are, or once were.

Grief, on the other hand, changes things. If you let it, it will aid the decomposition. I’m understanding by the millimeter why we are never the same after loss.

And yet, I feel as Rilke describes. Surrounded by stone. I understand why many harden, wanting to remain as we were, as it “was.”

Dear reader, there is a second verse to Rilke’s poem that is often left out:

“I don’t have much knowledge yet in grief

so this massive darkness makes me small.

You be the master: make yourself fierce, break in:

then your great transforming will happen to me,

and my great grief cry will happen to you.”

Rilke hands it over. In humility and surrender, he asks that the higher power of Grief itself break the darkness like a bolt of lightning, sparking the transformative process and uniting grief with its inherent dignity and divinity.

Perhaps this is all we can do when we’ve exhausted our own knowledge. We stop resisting and further wedging ourselves between the narrow stone walls. We stop minimizing our own experience and bravely surrender to its awesome power. We hand it over—to Weller, to Rilke, to Clifton, to Dillard, to the sea, to the sky, to the infinite guides who know our experience and will hold us through it.

It is an ancient path to walk. One clumsily stewarded by the modern village. One walked by entire cultures and communities who know we always must keep one face turned to the past, our tail in the sea.

Perhaps I don’t yet have a point more than this, a pretty bow to wrap this in. My broken bones are weight-beared; I am not yet re-made. I’m writing honestly, unhurriedly, painfully.

Have you told yourself lately that what you are feeling could be exactly right and right-sized even if you don’t yet, or ever, clearly understand why?

Perhaps what I can say from this little aquamarine house 12 months and two lifetimes apart is that the future comes by moving through the past. With dignity, forgiveness, and justice.

That the doorway Janus guards might be the one into our own interior underworld.

That there, a mighty river flows in stone, a buried sea of water in the Earth’s mantle four times as voluminous as what is currently held in all the world’s oceans, rivers, lakes, and ice combined.5, 6

+

I will come home to find your key on the kitchen table.

And yet, isn’t that how Franklin harnessed lightning?

“The descent beckons

as the ascent beckoned.

Memory is a kind

of accomplishment,

a sort of renewal

even

an initiation, since the spaces it opens are new places

inhabited by hordes

heretofore unrealized,

of new kinds—

since their movements

are toward new objectives

(even though formerly they were abandoned.)

– William Carlos Williams, excerpt from The Descent

A portion of all paid subscriptions goes to Mother Nation.

In Case You Missed It

If you’re new here, welcome! Take a wander through some of my favorite essays and poems below. Join as a subscriber and never miss an issue.

Stay Connected

• Email: izabellazucker@gmail.com

• Conduit Coaching—if my writing resonates, my other offerings might too.

While the tether between smell and memory are well known, eucalyptus oil, specifically, has been shown to improve memory performance by 226 percent. https://www.nad.com/news/simple-fragrance-boosts-memory-modifies-neural-connections

Weller’s third gate—the sorrows of the world.

https://www.etymonline.com/word/January

“Geologists have discovered buried seas in the Earth’s mantle. Four times as much water might be locked up there in a mineral called ringwoodite as is currently held in all the world’s oceans, rivers, lakes, and ice put together.” – Macfarlane, Underlands

The Earth’s mantle is predominantly solid, but it behaves like a very viscous, slow-moving fluid over geological timescales, allowing it to flow over millions of years. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earth%27s_mantle

This is so beautifully written and inspiring so much reflection. These lines brought tears to my eyes:

That the doorway Janus’ guards might be the one into our own interior underworld.

That there, a mighty river flows in stone, a buried sea of water in the Earth’s mantle four times as voluminous as what is currently held in all the world’s oceans, rivers, lakes, and ice combined.

Bearing the weight of these words, and this grief is such a gift. Thank you for sharing all that you do. There is beauty here for a few lifetimes