“I know it’s hard. The world is on fire, metaphorically and figuratively. However, it has always been on fire. There has never been a single author who had the immense luxury of writing at a time of absolute peace. And so choosing this work, you are entering a lineage of despair. And it’s up to you to turn the sentence into a medium from which we can understand each other and make something new out of this.” – Ocean Vuong, on creating during challenging times

Hi there,

I’m writing this essay during the week of June 9th, and the pressurizing sorrow and rage feel particularly palpable.

By the time this is edited and published, I suspect the feeling may have dissipated, whether through the millions who poured through the streets for No King’s Day protests, a cooling of the weather here on the Pacific Northwest coast, or the simple yet unexpected way someone replenished your humanity jar, however subtle.

It is a tricky thing, to write to meet the moment when the moment always morphs.

It is a more important thing, then, to slow down, to sink deeper, to acknowledge the urgency and say “yes, and.” To trace its origin to a more enduring, omnipresent story that’s asking to be told. To descend beneath the flare-ups and into the fissures that open as children of chaos, their energetic invitation both ancient yet fecund.1

In starting this essay, I didn’t want to lead with the horrors taking place as a hook. To piggyback on human suffering as a way to gain your attention out the gate, or as a means of somehow making my words more relevant, more timely, more important feels grossly exploitative.

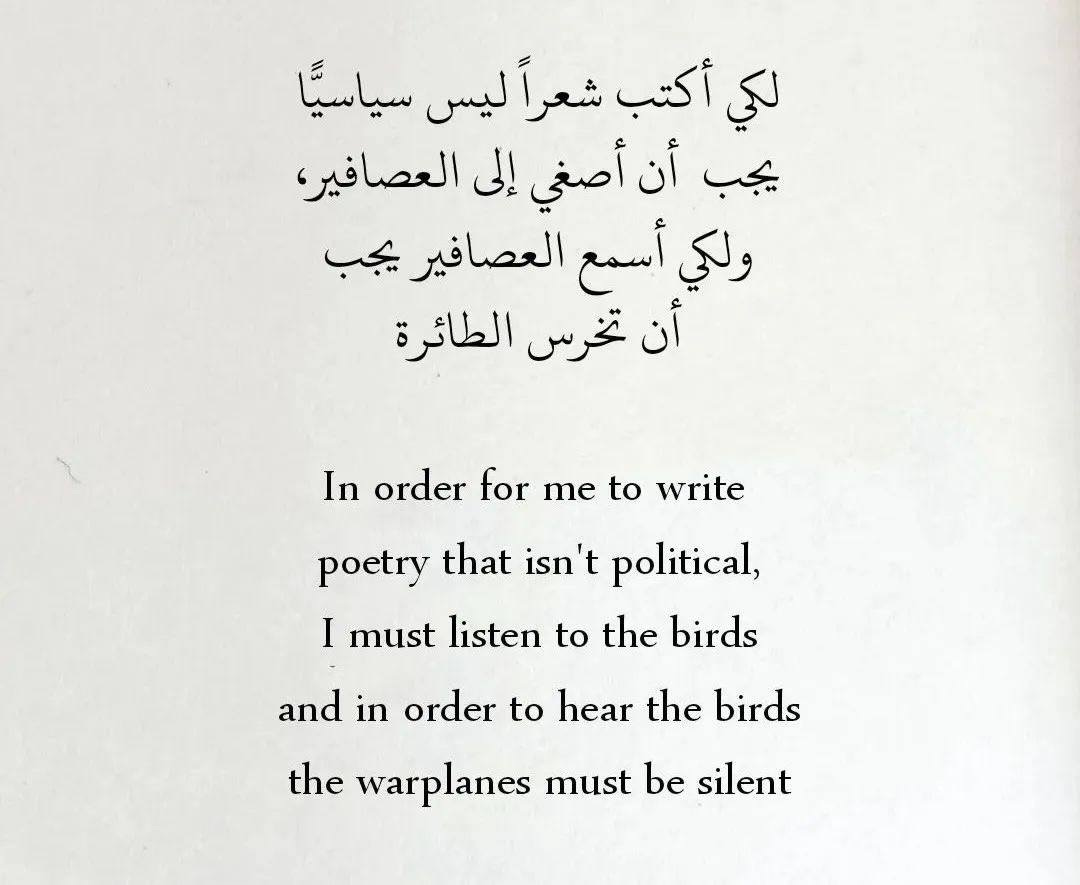

And yet, lately, it has felt impossible to write or share or really experience much of anything decontextualized from live-streamed atrocity.

How do we write, how do we create, how do we carry on with daily life as if any of it could exist in isolation or separation?

The answer is that it can’t.

The answer is that it doesn’t.

The answer is complexity and interconnectivity.

The result, I hope, is unbridled solidarity.

I know I am not alone in the freeze state that can come with engaging in a modern day digital news cycle and immersion in a dominant culture steeping in its own unhealed collective trauma. And this feeling of not-aloneness is enough to power a few more sentences on a day where, honestly, I really don’t know what I could possibly say.

On a day where I’m convinced my experience of detangling my feelings and privileges should exist nowhere close to the center of the narrative, let alone taking up space at all.

There are so many storytellers doing the necessary and dangerous work of truth-telling within a fascist regime, whether through investigative reporting and whistleblowing, searing analysis, and centering the stories and solutions of the people and places most impacted, as told by them. Go to them.

And yet, I write, because the alternative of waiting until things feels clear, less dire, or “like a better time” only strengthens the stifling, and I guess I do, for now, trust in this little corner of the internet. I know this month’s essay doesn’t need to be my “best,” so long as it adheres to this publication’s values of truth, integrity, and joy.

I know it can simply serve as a means of dispersing the pressure, a chisel to whatever hardening has taken hold.

I didn’t start this Substack so that it would only house my most perfect creations. I started it largely as a public-facing practice in vulnerability, accountability, and connection.

So today, I practice.

I practice re-centering in purpose and values, a motion that we can all take during times of upheaval and uncertainty.2

I practice being with unfinished ideas and semi-metabolized feelings, and publishing both alongside and in spite of them. Or rather, through them.

I practice falling apart, together.3

I practice playing my part as storyteller and weaver within a broader social ecosystem, and finding my edges as my activism evolves and interdepends alongside my becoming.

I recently took a road trip to western Montana, and had the luxury of turning the news cycle off for a few days. Inspired by the landscape, I wrote a little poem and posted it on Instagram once back online, having not yet checked the news.

Immediately after, I read stories and saw videos of that which I contemplated placing in the footnotes, but decided bears repeating: Palestinian people, starving, having survived ongoing genocide only to be killed while attempting to receive food (This is now a daily experience since the new U.S./Israel funded and operated aid facilities began, a far cry from international humanitarian aid norms); ICE agents abducting and detaining teenagers from vehicles on their way to volleyball practice; people lighting Jewish people on fire; and an elected official telling her constituents to calm down about losing healthcare because “we’re all going to die.”

Within the layers of horror arising in my body, I felt another layer of horror emerge, this one pungent with humiliation. How the fuck could I have just posted about wildflowers and rainbow trout? No mention of heartbreak, no mention of crisis, just fa-la-la foraging and poetic metaphor.

(Important note on the twisted role of social media platforms and the infiltration of the “personal brand” on the psyche. More on that some other time.)4

I immediately wanted to take it down in both self-disgust and fear of others’ perception, but instead sat with the sour taste, somehow recognizing the moment as Teacher.

The day went on, and I took a walk around the garden, the sage now fully in bloom. For the first time in a long time, maybe ever, I couldn’t appreciate the beauty. I didn’t feel I deserved it, the garden nor the beauty, not when bombs are being dropped. Not when people are dispossessed, herded, then killed anyway. Not when I’m here, born into this body, in this country, and them, theirs, all of us, still, together.

So I turned to another sage.

To

—literary hero, poetic expert on the relationship between joy and sorrow, and who just so happens to be an avid gardener. I was curious how his 2022 book of essays, Inciting Joy, would endure against the current (compounding) crisis(es), whose intensity seems to override both the body and history of all previous crises, as crisis often does.Upon flipping through the well-worn pages, I was weirdly grateful to be reminded that this book on joy was rampantly interwoven with slavery, imperialism, colonialism, and suffering.

It was joy with context, something I felt I had temporarily lost my ability to see.

“...we often think of joy as meaning ‘without pain,’...not only is it sometimes considered ‘unserious’ or frivolous to talk about joy (i.e. But there’s so much pain in the world!,) but this definition also suggests that someone might be able to live without—or maybe a more accurate phrase is free of—heartbreak or sorrow…but what happens if joy is not separate from pain? Or even more to the point, what if joy is not only entangled with pain…but is also what emerges from how we care for each other through those things?”

So, then, admiring late spring wildflowers not as a shallow activity for dissociation and ignorance, but as practice in recognizing their benevolent ability to brighten something deep within us despite It All.

Admiring the way in which the garden generously holds space for me, the way it lets me tend and practice the most basic tenants of care. Expanding this admiration to the entire Earth, the most fertile ground, literally, for which we might explore care and purpose.

Maybe when we behold beauty we remember we are also being held by it. That when we behold beauty, what we are actually beholding is care, which we all deserve. That a capacity for care might be encoded into every living being, seen and unseen. That it is not selfish to experience this in a flower or a fish, but actually a form of attentive reciprocity. That we can descend into a truer definition of beauty, one far deeper than the visual and into the visceral—the core essence in which all was created.

Maybe.

And yet, the guilt works its way in through the gut-wrenching reality of injustice. How might Ross, and joy, guide us here?

“...one thing I want to be cautious of—by which I really mean refuse—are the ways we sometimes consider, for instance, gardening (or health or healthcare or potable water)...a privilege, which actually obscures the fact that to be without…is violence…rather than indulging in virtue signaling that simply reifies or maybe even enjoys the guilt of so-called privilege…how about instead we figure out how to get rid of disprivilege…

Or to say it another way: rather than cursing the darkness, what if we planted some seeds?”

Transmute the guilt into action that actually serves and seeds.

That actually creates amidst status quo stagnation.

The transmutation is work that cannot be leap-frogged. It must be moved through. Only then can we actually make space for meaningful, grounded action that extends beyond the acute guilt-ridden flare-up and into sustained allyship and co-resistance rooted in accountability.

This requires the work, as Ross writes, of understanding how identity privilege operates within existing systemic structures (i.e. white, able, cis, hetero, and/or male-bodied; born into U.S. citizenship; of upper class/generational wealth) as both distinct from yet deeply interconnected to resource access (i.e. safety, education, economic opportunity, healthcare and health outcomes, clean air and water, etc.). i.e.: What many privileged folks feel guilt over is actually just a basic human need being met within a system designed around profit, not people.

The garden, then, which is access to fresh food, to peaceful and creative space, to land, is less a privilege and more an opportunity that’s more easily accessed because of what my body and my economic status can provide me within a settler colonial state.

Re-framing the “have/have not” conversation as a result of systemic violence allows for greater awareness between a power-over, supremacist paradigm, and one that, at a minimum, can easily met our most fundamental needs.

It sounds ludicrous to let another’s fundamental need not being met be what radicalizes us into action, and yet, sadly, and it can do just that.

Guilt, while it can be an important indicator, largely gets in the way of more important work, that, at its utmost core, is love. It often prioritizes the comfort of the privileged over the truth of the oppressed, blocking meaningful opening, healing, and change.

Guilt keeps us stuck in the status quo. Guilt serves the status quo.

And guilt is often my cue to grieve.

Again, Gay guides:

“It seems to me that grief is not gotten over, it is gotten into. And the griever teaches us, or reminds us, there is no pulling it together. There are only degrees or expressions of falling apart…

…When we witness the learning, the changing, the grieving, with curiosity and patience and care and love; when we make room for and witness and invite each other’s unfixing…when we join in grieving, and when we do it again and again, making of that soft, mutual, curious, ground-less witnessing not only an endeavor, but also a practice…we fall into each other. And when we catch the grave light shimmering from the tethers between us when it happens…this holding each other through the falling, I am pretty sure of this, one of the names anyway: joy.”

In a current world order of cyclical violence born from undigested grief and trauma, I grieve into the truth that it didn’t have to be like this. It still doesn’t. And for so long, it wasn’t.

I wonder who we might be before the soul-wound started, and after the healing is done? Beneath the pain, beneath the guilt and shame, beneath all that we’ve banished? What then?

There are many who already know.

Many who keep the wisdom, who keep the stories, who’ve survived the unsurvivable, and who have never lost the Connection. It is within the Indigenous Peoples across the globe, within the lands and waters themselves, and deep within all of our marrow, too.

Last year, I took part in an online workshop with Dr. Lyla June Johnston, an artist, scholar, and activist of Diné (Navajo), Tsétsêhéstâhese (Cheyenne) and European lineages, and in whose poetry I will leave you.

A fellow student asked a question about finding awe, framed in a way that at the time, my reactive self judged to be far too trivial a question. This was the Lyla June. I’ll never forget how warmly and generously Lyla responded, sharing the teaching of hózhó—the concept of beauty that is the central organizing principle within Diné cosmology and culture.

It is said to be among the most important words in the Navajo language.

The topic of her lecture was about how the world needs organizers who know how to channel the power and imagination of the social and ecological communities around us, weaving their strengths into a strong, collaborative tapestry.

Had I forgotten then, as I had now, that the thread, could be beauty?

“Her voice

hums in my blood

quiet as a stream in the night

and it is a song about how

we are all

just

so loved.

The eagles dip their talons into Her soft body

and pull from it a fish, a fleshmeal for the children.

They sing this grandfather song with her

and it sounds like feathers

cutting into the sky.

And it is this song about how even

hatred will surrender

to wonder.

She is breaking my granite heart apart with her water

and even the hardest doubts and sorrows

are breaking and giving way to

Her infinite grace.

And who knew that

sometimes grace can come in the form

of a raging river.

And when it rips away everything

that you thought you owned

all the pain, all the blame, all the shame

and replaces it with a weightlessness

so profound you can’t not cry

tears of absolute praise

and run all around the river banks shouting to the

the cattails and the minnows and the willows

about the truth of beauty?

– excerpt from “And God is the Water” by Dr. Lyla June Johnston

A portion of all paid subscriptions goes to Mother Nation.

In Case You Missed It

If you’re new here, welcome! Take a wander through some of my favorite essays below. Join as a subscriber and never miss an issue.

Stay Connected

• Email: izabellazucker@gmail.com

• Conduit Coaching—my new business!

Intrigued by fissures? Check out the work of Dr. Bayo Akomolafe.

If you’re feeling called to reconnect with purpose and values, whether through the medium of your life or your work, and are interested in support along the journey, I invite you into my new home, Conduit Coaching.

Concept of “falling apart together” pulled from “Grief Suite” chapter of Ross Gay’s, Inciting Joy.

“Ultimately, I argue for a view of the self and of identity that is the opposite of the personal brand: an unstable, shapeshifting thing determined by interactions with others and with different kinds of places.” – Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy

So beautiful, so healing, so needed. This is one I will return to often. Thank you.